British actor Corin Redgrave died April 6 in a south London hospital, three months shy of turning 71. He was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2000 and suffered a major heart attack in 2005. However, he recovered sufficiently to be able to return to the stage in 2009 and apparently was in discussion about future theatrical projects.

According to news accounts, he fell ill again recently and died surrounded by family members, including his wife, Kika Markham.

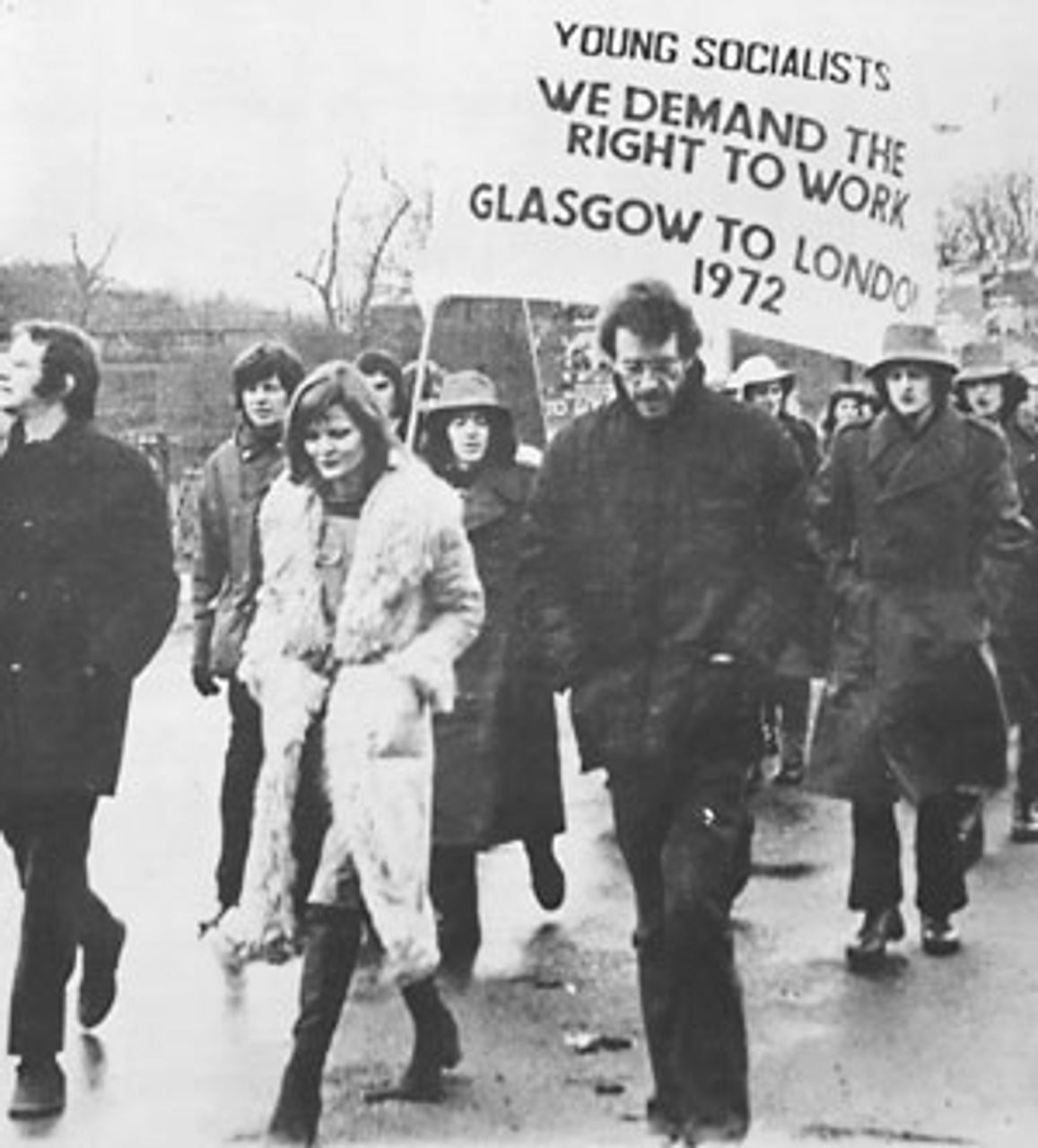

SLL Glasgow to London jobs march in 1972, film

SLL Glasgow to London jobs march in 1972, film

director Ken Loach on the left, Redgrave on the right

Redgrave, along with his sister Vanessa, was among the most prominent members of his generation of British artists and intellectuals attracted in the late 1960s and early 1970s to the Trotskyist movement—the Socialist Labour League (later the Workers Revolutionary Party), led by Gerry Healy. Many sacrificed careers and celebrity in the service of what they believed to be the socialist future.

The engagement by these artists in the Marxist movement was the high point in Britain of a period of extraordinary intellectual and cultural ferment. British imperialism emerged from World War II economically bankrupt. The Empire was falling apart. The working class was on the move—and its disgust with the decrepit aristocracy, and the ruling establishment in general, found artistic expression.

Vanessa Redgrave campaigning as a WRP candidate

Vanessa Redgrave campaigning as a WRP candidate

in 1974

The purposelessness of bourgeois life and the hypocrisy of British institutions became targets of relentless cultural criticism—angry, sarcastic, iconoclastic and rebellious. The “Angry Young Men” of the mid-1950s, a group of working-class and lower-middle-class writers, including John Osborne, Kingsley Amis, John Braine and Alan Sillitoe, expressed bitterness and disillusionment with British society. Richard Burton was one of the most prominent and talented performers identified with this trend.

The “British New Wave” of the early 1960s developed a good many of these themes in film and television, generally in a more distinctly left-wing form, in works such as Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life, Karel Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, and Tony Richardson’s The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (the last two films were based on works by Sillitoe). New acting faces and voices were associated with this “neo-realism,” including Albert Finney, Tom Courtenay, Alan Bates, Rita Tushingham and Richard Harris.

The work of the period was artistically uneven, but usually forthright and provocative. With all its failings, much of it remains in the memory, and some of the imagery was quite haunting. In this environment, British cinema and theater looked into the life of the working class in a manner that was, at its best, realistic and unsentimental. At any rate, these qualities were far more present in Britain than in the US.

This was a rare moment, expressive of a state of increasingly revolutionary turmoil.

Within this context, it is necessary to stress the extraordinary role of the Socialist Labour League (SLL) and Healy in particular. It was not accidental that so many artists came around the SLL. It was the only revolutionary party in Britain—it was also the only honest one. The British Trotskyist movement, in which Healy played the decisive role, emerged out of decades of struggle against the Labour Party and Stalinism. Moreover, it brought into the milieu of artists, writers and intellectuals something that was otherwise absent—a historical perspective.

For many years Healy, whose role was fictionally memorialized by Trevor Griffiths in his 1973 play The Party, upheld a revolutionary socialist perspective against all comers.

Corin Redgrave, of course, came from an acting family with deep roots. His paternal grandfather, Roy Redgrave, was a stage and silent screen actor who died in Australia in 1922. His paternal grandmother, Margaret Scudamore, also performed.

Corin’s father, Michael Redgrave (1908–1985), was one of the most distinguished British stage and screen performers of his remarkable generation (Laurence Olivier, John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson, Alec Guinness). Michael’s wife, Rachel Kempson (1910–2003), was also a celebrated actress on the stage and screen.

Corin Redgrave’s sisters, Vanessa (born 1937) and Lynn (born 1943), are both prominent performers, and the next generation has produced Joely and Natasha Richardson (daughters of Vanessa and film director Tony Richardson)—the latter of whom died in a tragic skiing accident last year—and Jemma Redgrave, Corin’s daughter with his first wife.

It seems reasonable to suggest that Corin Redgrave lived (and performed) in the shadow of his father and more famous older sister for a good deal of his life, or, in any case, that this was the public perception that he had to confront.

After graduating from King’s College, Cambridge, Redgrave began his acting career at London’s distinguished Royal Court Theatre in 1961, at the age of 22, in a production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. His first credited film or television performance came in an episode of “The Avengers,” in 1964.

He subsequently appeared in supporting roles in a number of Vanessa Redgrave’s films, including A Man for All Seasons (1966), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), and Oh! What a Lovely War (1969), and in one alongside his sister Lynn, The Deadly Affair (1966).

Redgrave also had a role in Mario Monicelli’s La ragazza con la pistola (Girl With a Pistol, 1968), which starred Monica Vitti. Excerpts from this sometimes amusing film, as well as portions of A Man for All Seasons, are available for viewing on YouTube.

The young Redgrave impresses one as intelligent and imposing, but a little stiff and self-conscious. He did not possess the charisma, the commanding presence, and perhaps the native gift of his father and sister—he had to work harder at his acting. Or, to put it another way, he was somewhat more thoughtful.

A professional actor is obliged to work on all sorts of material—good, bad and indifferent. For a performer to give his all, he must be more or less at one with the piece in question. With the early Redgrave, one cannot entirely avoid the suspicion that he often, rightfully, considers his lines inadequate or even banal. He tries to look convinced of their ineffable character, but sometimes fails. He often appears smarter than his material, a difficulty for an actor.

Redgrave participated in anti-Vietnam War demonstrations in London, a number of which were led by his already prominent sister, in the late 1960s. He encountered the Socialist Labour League around 1970. He was already sufficiently engaged to play a role (as narrator) in the first major effort undertaken by the actors and entertainers who had come around the SLL at the large Alexandra Palace “Anti-Tory Rally” in February 1971, where they staged a satirical-musical piece on “200 years of Labour History.”

Again, it is worth recalling some of those who gravitated to the SLL: film and television directors Ken Loach and Roy Battersby; writers Jim Allen, Trevor Griffiths, John Arden, Margaretta D’Arcy, David Mercer, John McGrath, Colin Welland, Neville Smith, Tom Kempinski and Troy Kennedy Martin; producers/editors Tony Garnett, Kenith Trodd and Roger Smith; innumerable actors, including the Redgraves, Tony Selby, Jack Shepherd, Frances de la Tour, Malcolm Tierney, David Calder, David Hargreaves, etc.; journalist Francis Wyndham; artist and photographic archivist David King; and countless others.

Those who at least participated in theatrical performances or Young Socialist fairs, or lent their names to fund-raising activities, included actors Judy Geeson, Eleanor Bron, Judi Dench, Glenda Jackson, Marty Feldman, Dudley Moore, Suzi Kendall, Helen Mirren, Roy Kinnear and Anthony Booth; poets Adrian Mitchell and Christopher Logue; comic Spike Milligan; singers Annie Ross and Paul Jones (former lead singer of Manfred Mann); rock bands Slade and UB40, among others; harmonica legend Larry Adler; talk show host Michael Parkinson; and so forth.

Corin Redgrave was one of those artists and intellectuals who made the most serious effort to study Marxism and Trotskyism, to provide his activity with a theoretical grounding. Many of the actors who participated in the activities of the SLL-WRP, including his sister Vanessa, were far more content to rely on their intuition. To simplify matters, one could say that to those who knew him, while Vanessa Redgrave was always acting, her brother was always thinking.

Vanessa was always able to call on her inexhaustible supply of dramatic gestures and flourishes. She could be, at any given moment, Antigone, Cleopatra or “The Lady From the Sea.” Corin was almost the precise opposite. A shy and reserved man, he spoke quietly, with long pauses as he searched for the proper words, drawing deeply on a cigarette.

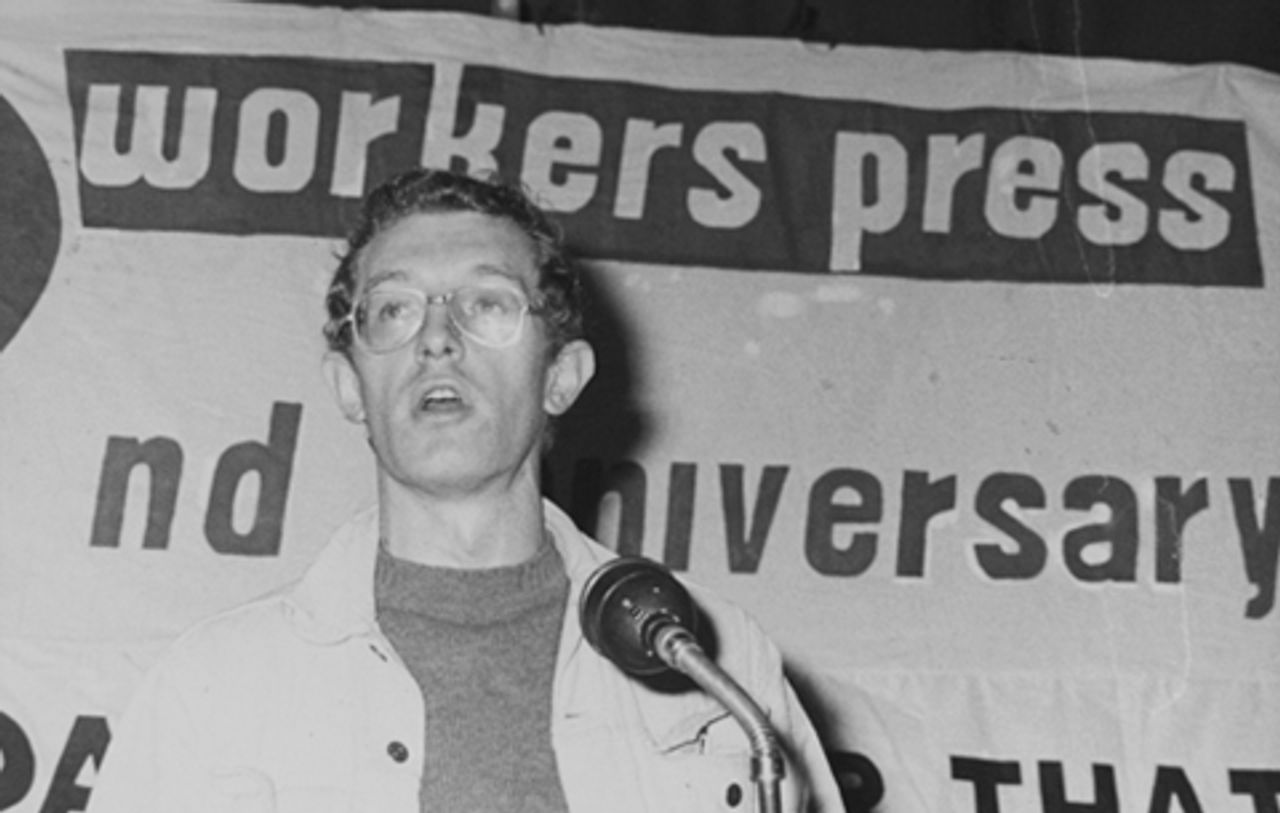

Corin Redgrave at rally for the daily Workers Press in 1971

Corin Redgrave at rally for the daily Workers Press in 1971

Corin Redgrave began to participate seriously in political life in 1971. On July 1 of that year, two weeks before his 32nd birthday, as part of a series of readers’ comments in the daily newspaper of the Socialist Labour League, Redgrave explained “Why I read the Workers Press:”

“I read the Workers Press to find out what’s happening. In four pages it gets nearer the essence of the situation than other papers do with 20 pages. But then again that is not the object of other papers.

“Under the guise of ‘unbiased objective reporting’ their purpose is to blind readers to any need or possibility of changing the way things are, save in their most inessential features.…

“Fleet St. newspapers have the life cycle of the May fly. What begins as information ends as dead litter.

“But knowledge, unlike information, is a matter of continuous development. That is where the features on the inside pages [of the Workers Press] are so valuable.

“They take on historical, philosophical and scientific subject matter and follow it through.”

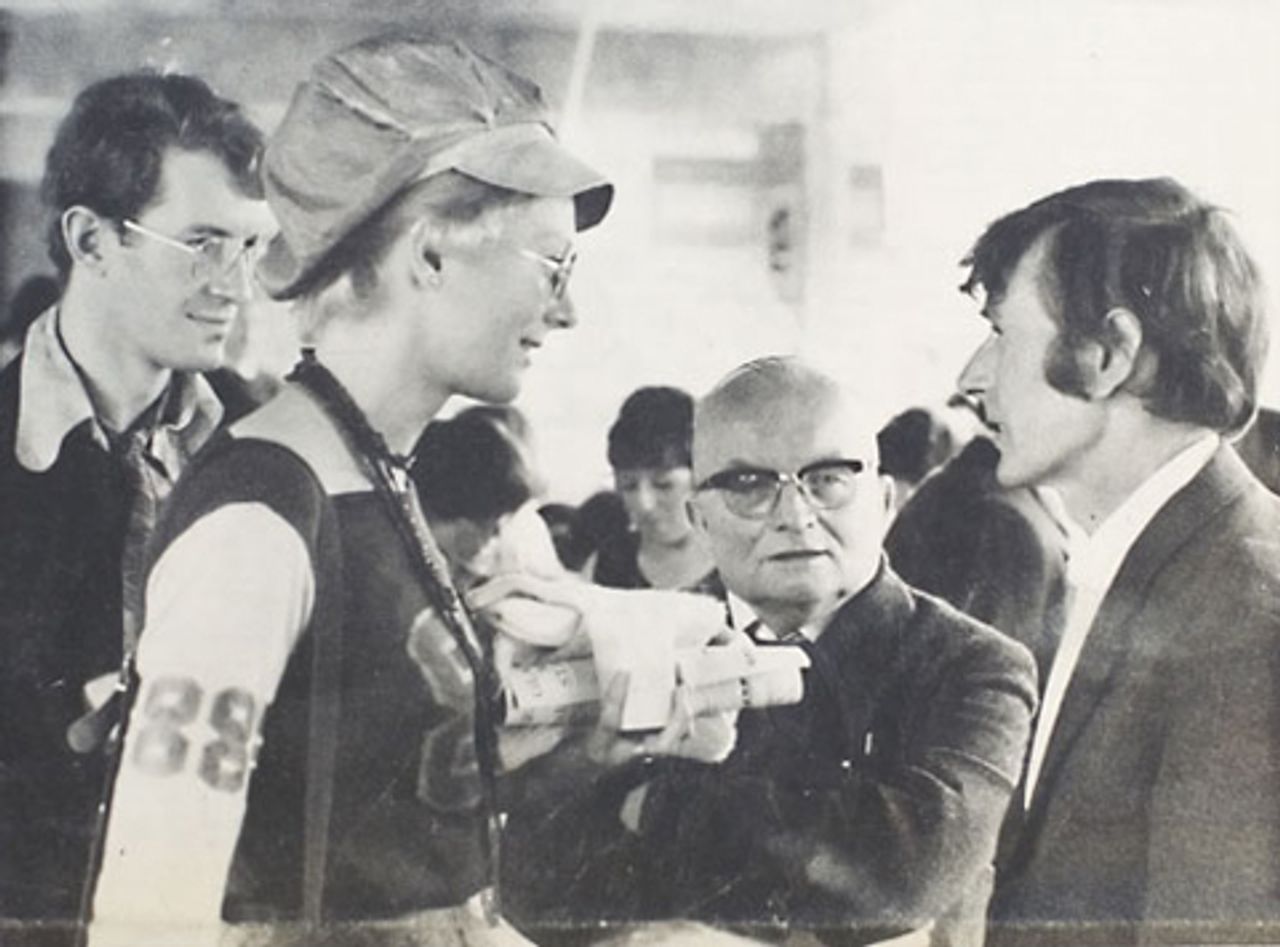

Corin and Vanessa Redgrave, SLL leader Gerry Healy, and victimized glass worker Gerry Caughey in 1971

Corin and Vanessa Redgrave, SLL leader Gerry Healy, and victimized glass worker Gerry Caughey in 1971

On the front page of the July 12, 1971, Workers Press we find a poignant photo. It shows Corin and Vanessa Redgrave, Gerry Healy and Gerry Caughey, a victimized striker from Pilkington’s, the glass company. In the photo, Vanessa is still dressed rather flamboyantly, something out of “Swinging London,” but already—although her relationship to the movement was still quite tenuous—dominates the image. In fact, as Vanessa Redgrave once acknowledged, it was Corin who subjected her own doubts and evasions to relentless criticism, and finally convinced her to join the SLL.

The Redgraves found themselves in agreement with the revolutionary perspective of the International Committee of the Fourth International (ICFI) and its orientation toward the building of a movement based on socialist principles in the working class, and attempted to act on that conviction.

There were, however, different sides to that process. The upsurge of the international class struggle, and the artistic upheaval it generated, brought many intellectuals toward the Trotskyist movement in Britain. The conditions encouraged and made possible the entry of an entire layer, including even elements from the cultural “aristocracy” such as the Redgraves, into revolutionary politics.

Nonetheless, that didn’t solve all the difficulties lodged in the political situation. Corin Redgrave’s subsequent development became ensnared in the growing contradictions of the SLL (the WRP after November 1973). Those, in turn, were bound up with the existing, generally unfavorable conditions for the Marxist tendency: the continued dominance over broad sections of the European and international working class of Labour, Stalinist and trade union bureaucracies and the relative isolation of the genuinely Trotskyist forces.

Serious political problems were emerging in the SLL in the early 1970s, when the Redgraves and most of the artists were still very inexperienced—not only practically but also theoretically. They were enthusiastic, even extremely dedicated—but they knew little about the history of the international Trotskyist movement. Moreover, although neither Vanessa nor Corin Redgrave was a snob, their life experience did not include any serious contact with the struggles of the working class.

Healy and the SLL stood virtually alone for a time in their indefatigable determination to construct a revolutionary party independent of the labor bureaucracies, bourgeois nationalists, Castroists, Maoists, etc. The SLL, after its resolute stand in the early 1960s, began to backslide in a national opportunist direction in the early 1970s. The unclarified split with the French Organisation Communiste Internationaliste (OCI) in 1971, its principal allies in the struggle in the early 1960s against Pabloite opportunism, added to the SLL’s practical and theoretical difficulties.

Healy and the SLL leadership developed an increasingly nationalist perspective, proceeding as though their task was primarily to build up the forces and resources for a British revolution, and putting on the back burner the theoretical and practical questions bound up with the construction of a world party. The SLL’s leader began to indicate, in his speeches, an orientation more and more exclusively to the interests and needs of the “English workers.”

The developing political crisis within the SLL/WRP certainly undermined the political education of Corin Redgrave and other artists in the party. Moreover, Redgrave virtually stopped acting—partly as the result of an apparent industry blacklist. Between the mid-1970s and 1990 he has only a handful of television and film credits.

The conception that artistic activity and revolutionary politics are mutually exclusive, which was not the official policy of the SLL, but in practice determined the choices made by a number of its artist-intellectual members, is false. Especially in the case of someone like Redgrave, for whom acting was “in the blood,” such a move had to have harmful, even debilitating consequences.

One of the theatricals produced by actors sympathetic to the SLL, on the English Revolution of 1640, in 1972

One of the theatricals produced by actors sympathetic to the SLL, on the English Revolution of 1640, in 1972

In the early days, Corin participated in the various theatrical pageants staged by the actors’ group, on the Cromwellian revolution, the Russian Revolution, the Depression years, Stalinist repression in the Soviet Union, etc. The artistic value of these works, some of which he co-wrote or directed, was mixed. Amusing and pointed satire, along with the serious effort to recreate critical historical events, co-existed with rather crude agit-prop.

Both Redgraves were elevated rapidly, too rapidly, into the leadership of the WRP in the mid-1970s, eventually becoming members of its Central and Political Committees. The election of the Labour Party in 1974 precipitated a crisis in the WRP, leading to the departure of Alan Thornett and a portion of the trade union cadre, who had organized an opposition to Healy on an essentially right-wing basis. The Redgraves and others from the artistic milieu played an even larger role after that crisis.

One of the chief weaknesses of the Healy leadership’s interaction with the artists in the early 1970s was its failure to probe any of the serious theoretical and aesthetic issues raised by Trotsky and Aleksandr Voronsky in the 1920s and 1930s. The heavy-handed Stalinist methods of “proletarian culture” and “socialist realism” were rejected out of hand by the British Trotskyists, but unaccompanied by any sustained effort to criticize or transcend the somewhat provincial approaches with which British actors and writers felt most comfortable: on the one hand, “kitchen sink” drama (i.e., empirical, surface realism), and, on the other, the grand declaiming style, with all its strengths and weaknesses, associated with mounting Shakespeare’s works and other classics.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, those who worked with Redgrave in the movement could see that he was in real political and personal crisis. Assigned to undertake work as a party organizer, he floundered—and, to make matters worse, he was often the subject of Healy’s angry and subjective outbursts.

Healy’s treatment and use of the Redgraves and others took on, as the 1970s unfolded, an ever more opportunist character. After Labour’s 1974 victory in Britain, and the general “normalization” of European political life, including the betrayal of the Portuguese revolution in 1974 and the relatively uneventful transition from Francoism to bourgeois democracy in Spain, Healy and his colleagues in the WRP leadership, Michael Banda and Cliff Slaughter, grew increasingly pessimistic about the revolutionary capacities of the British and European working class. They turned with growing enthusiasm toward the bourgeois nationalist movements, especially in the Middle East, and toward the trade union bureaucracy in Britain.

The Redgrave name, particularly Vanessa’s, became an important calling card, opening or seeming to open a variety of political and financial doors.

What had been the spontaneous enthusiasm of actors and writers in the early 1970s toward the production of various theatrical and musical events became something more cynical by the time, for example, of a show staged at the WRP’s Marx Centenary in 1983 (to mark the 100th anniversary of Marx’s death). “Stars” were parachuted in at the last moment to replace young people and lesser-known actors who had spent weeks rehearsing the Marx piece. This was part of a general opportunist decay.

By the late 1970s, Corin Redgrave had become one of the party’s main public spokesmen. He was obliged to represent the WRP when it came under attack by the British media and the state.

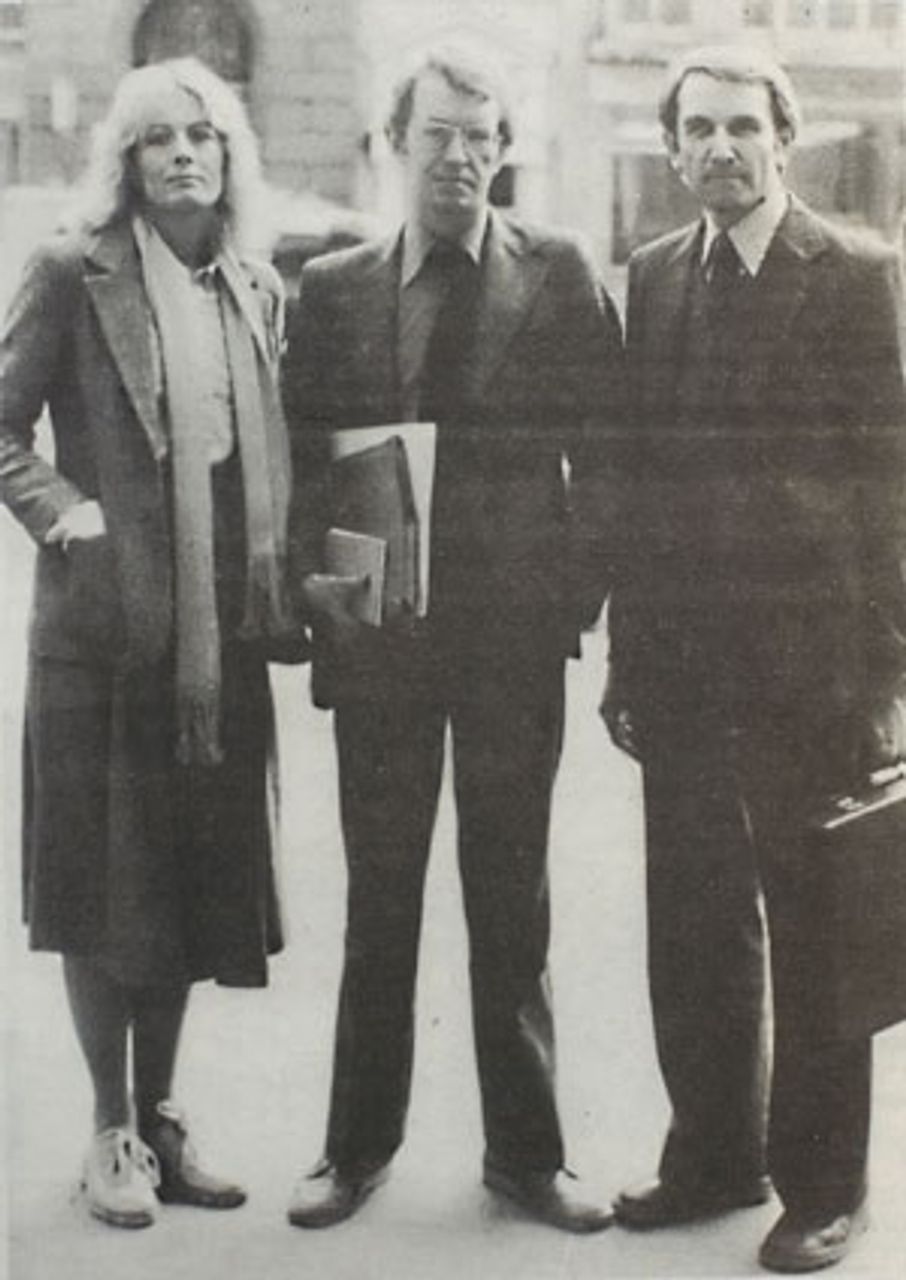

Corin and Vanessa Redgrave at the time of the

Corin and Vanessa Redgrave at the time of the

Observer libel trial in 1978

In September 1975, the Observer newspaper carried a defamatory article alleging that the WRP was an “extremist” group hiding a cache of arms at its College of Marxist Education. This provocation was planned to coincide with a police raid on the College. The WRP’s campaign to defend itself won overwhelming support within broad sections of the organized workers’ movement and large sections of the intellectual and artistic community. The party legitimately sued the Observer for libel, and the case came to trial in October-November 1978.

Vanessa and Corin Redgrave, Roy Battersby, during

Vanessa and Corin Redgrave, Roy Battersby, during

the Observer trial in 1978

Redgrave, along with his sister and Roy Battersby, played the principal role in the case on behalf of the WRP. Neither Healy nor Banda made an appearance. Notwithstanding the difficulties of proving such a libel case, Redgrave made far too many concessions in the direction of proving the WRP’s “respectability” and abhorrence of violence.

In the early 1980s, Redgrave suffered something of an inevitable personal crisis and attempted to return to acting, while remaining politically active. The WRP by this time was in a state of severe crisis, and for the first time facing political and theoretical opposition to its opportunist course within the International Committee of the Fourth International, from the Workers League in the US.

Redgrave, who had little contact with the international Trotskyist movement and whose study of Marxism and the history of Trotskyism had either been halted or had made little progress in the opportunist environs of the WRP, did not grasp the issues that arose in the split of 1985-1986. He returned to active involvement in the WRP at a very bad time—as the crisis erupted.

Strangely, he was at Healy’s side in August 1985 and sought to mislead ICFI delegates with a report that falsified the cause of the financial crisis that had suddenly erupted. Redgrave left the Trotskyist movement with Healy in the autumn of 1985. For all intents and purposes, that was the end of his serious political life.

After Redgrave’s departure from the WRP, there is only a series of peculiar and abortive efforts on his part to keep a group of actors around Healy in the short-lived “Marxist Party,” then later, the inevitable drift into social liberalism. He remained a protester on various issues—the Palestinian question, racism, Chechnya, “world peace.” As has happened to so many on the left, he found his way back to a quite common brand of British philanthropic do-gooding.

Redgrave also found his way back to the theater. He carved out a niche as a character actor—in which he performed well and often sympathetically. Perhaps, at some personal level, he drew something from the conflicts and contradictions through which he had passed. And perhaps as well, there is some truth to the press accounts of his life that point to the “liberating” effect of his father’s death in 1985 on his own artistic personality.

Following his “rehabilitation” in the late 1980s, when it was no longer the case, in the words of the Daily Telegraph, that “most directors regarded him as [politically] too hot to handle,” he appeared successfully in theater, television and film. In works such as In the Name of the Father (1993), Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994), Persuasion (1995) and The Forsyte Saga (2002), he performed admirably. In the generous phrase of a BBC obituary, “he bloomed later than Vanessa, who soon became an international star, yet went on to be regarded as one of the country’s greatest character actors.”

As far as his political and social views are concerned, the general picture was clear—Corin Redgrave had more or less made his peace with the status quo, and vice versa. Whether or not he had shifted as far as his sister, who fawned over Prince William and the royal family at a recent awards ceremony, is unknown to us, but not the most critical matter.

The Redgraves’ evolution and the evolution of many of the artists and intellectuals drawn to revolutionary politics in Britain in the early 1970s have their tragic element. This was collectively an enormously talented and humane collection of human beings, in fact, the best of their generation.

Individuals are responsible for what they do, both the “evil” and the “good,” but what they do is strongly influenced and shaped by events and processes outside them. We pay tribute to what was best and most self-sacrificing in Corin Redgrave and the generation of artists of which he was a significant representative.

The authors also recommend: