May 4 marks the 40th anniversary of the shootings of unarmed student protesters at Kent State University in northeast Ohio. The Ohio National Guard killed four students and wounded nine others at a rally against the Nixon administration’s decision to escalate the Vietnam War by invading neighboring Cambodia.

The four students who were killed by National

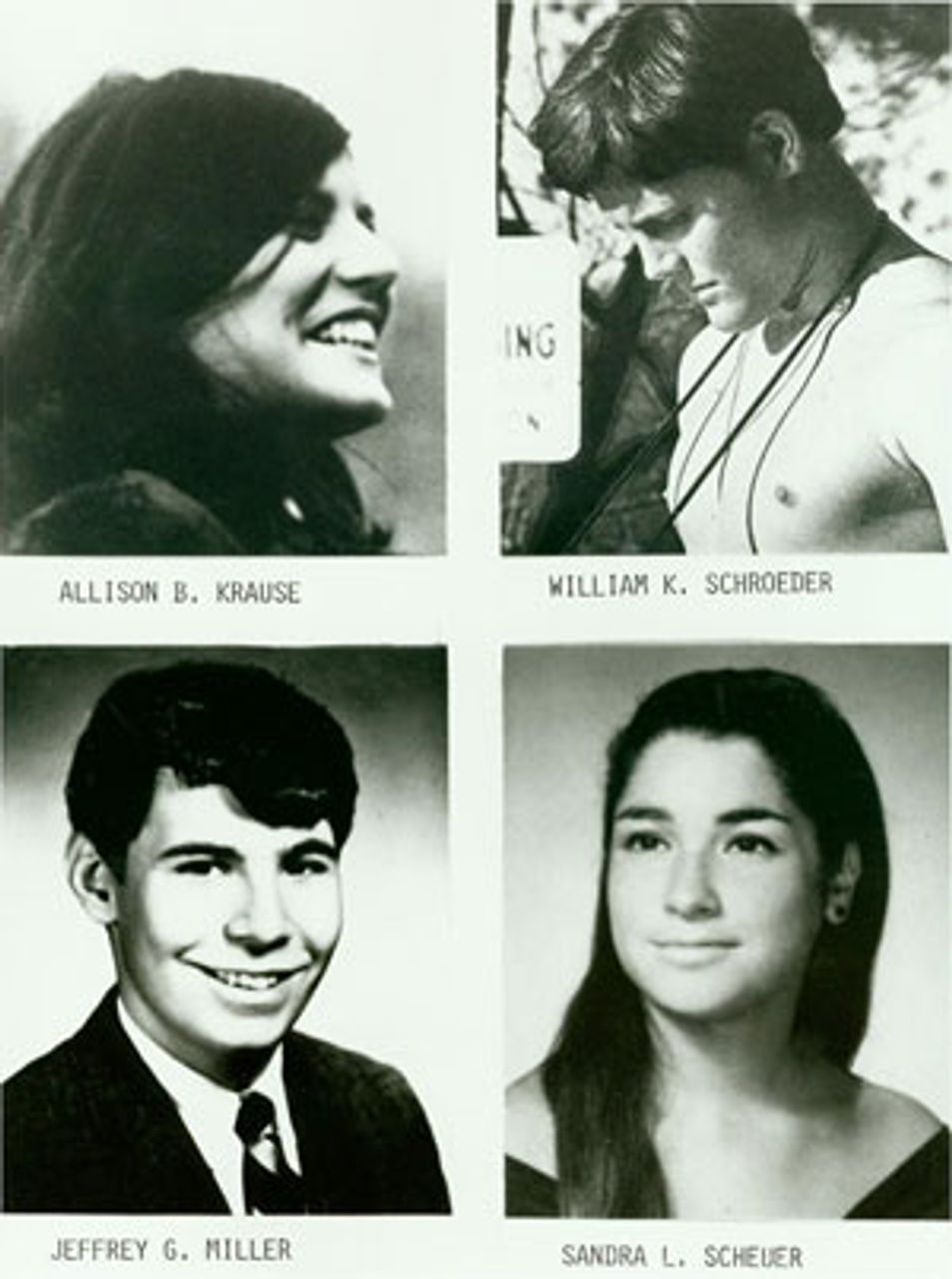

The four students who were killed by National Guardsmen at Kent State, May 1970. More images

can be viewed here.

The four students who died were Allison Krause and Jeffrey Miller, who had participated in the antiwar protest, and two bystanders, Sandra Scheuer and William Schroeder, who were walking between classes when the troops opened fire. Miller was killed instantly, Scheuer died within minutes, while Krause and Schroeder succumbed to their wounds after several hours.

One of the students wounded, Dean Kahler, 20, was a first-semester freshman who was a curious onlooker to the protest. A bullet cut his spinal column, leaving him in a wheelchair to this day.

At least 67 bullets were fired during the 13-second fusillade, and students were hit over a wide area. The closest of the victims, one of the wounded, was 71 feet from where the troops formed a firing line. The furthest, wounded in the neck, was 750 feet away. The four dead students were between 265 and 345 feet distant. None of the victims was armed or could have posed a physical threat to the guardsmen.

The Kent State Massacre was part of a wave of violent state repression that swept the United States in the aftermath of the April 30 television announcement by President Richard Nixon that US forces had crossed the border from Vietnam and invaded Cambodia.

The imperialist war had been raging at full force for more than five years, amid growing popular opposition in the United States, as the US casualties mounted into the tens of thousands and Vietnamese casualties into the millions. The invasion of Cambodia triggered a wave of mass protests against the war across the country. The murderous response by the forces of the state amounted to bringing the war home against the American people.

A week after Kent State, National Guard troops and state police shot to death six black students and wounded dozens of others in Augusta, Georgia, after a protest over the murder of 16-year-old Charles Oatman, a mentally disabled black youth who was beaten to death in the county jail. The troops and police were ordered into the city by Democratic Governor Lester Maddox, a notorious segregationist.

Three days later, police and state highway patrolmen fired automatic weapons into a dormitory at Jackson State University, a historically black college in the Mississippi state capital, killing two students and wounding nine others. Phillip Lafayette Gibbs, a 21-year-old junior at the school, and James Earl Green, a 17-year-old student at a nearby high school, were shot dead.

What happened in Ohio

At Kent State, about 50 miles south of Cleveland, 500 students gathered for a protest on May 1, the day after Nixon’s national television speech. Demonstrations escalated, and on the evening of May 2, the Army Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) building on campus was set on fire and burned down. Kent Mayor Leroy Satrom declared a state of emergency and asked Ohio Governor James A. Rhodes to send in the National Guard.

The troops were in the vicinity already because they had been mobilized by Rhodes in an attempt to smash a strike by Teamster truck drivers in Akron. They arrived in Kent within hours, accompanied by armored personnel carriers, and immediately clashed with more than a thousand demonstrators. The 900 troops began firing hundreds of rounds of tear gas and threatening the crowd with their bayonets, wounding one student. More than 100 students were arrested, the majority for violating the 8 p.m.-to-dawn curfew imposed by the city government.

On Sunday, May 3, Governor Rhodes himself arrived in Kent to supervise the suppression of the antiwar protests. Hundreds of demonstrators staged a sit-in on an intersection near the campus, pressing demands for abolition of ROTC, a cut in tuition, amnesty for all those arrested and removal of the guardsmen from the town. The troops used tear gas and bayonets to break up the demonstration and drive the students back on campus.

Rhodes told a press conference that day that the antiwar protesters were “worse than the brown shirts and the communist element and also the night riders and the vigilantes. They’re the worst type of people that we harbor in America. I think that we’re up against the strongest, well-trained, militant, revolutionary group that has ever assembled in America.”

He said he would ask the Ohio state legislature to make throwing rocks at police and firemen a felony crime and require automatic expulsion or firing of any student, teacher or university employee convicted of participating in a “riot.”

On Monday, May 4, campus officials tried to ban the scheduled noontime rally, but about 2,000 students gathered anyway. The Guard was ordered to disperse the students, who defied tear gas and threats of arrest. Hundreds of students continued to confront the soldiers, and at 12:24 p.m. the guardsmen took aim and opened fire.

The aftermath of the massacre

The Kent State massacre had a politically galvanizing effect upon millions of young people, who reacted to the killings with outrage and anger. An unprecedented nationwide student strike erupted, involving an estimated 4.3 million students, shutting down or disrupting more than 900 college campuses. The National Guard was dispatched to 21 campuses, while police battled students at another 26. University officials closed down 51 campuses for the remainder of the term. The Kent State campus remained closed for six weeks.

On the following weekend, well over 100,000 people demonstrated in Washington, D.C. Nixon administration officials, huddled in their offices, with National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger declaring that the US capital “took on the character of a besieged city.”

Following the shootings, the White House blamed the killings on the students themselves. Nixon’s press secretary Ron Ziegler, speaking on behalf of a president whose hands were dripping with the blood of the Vietnamese people, said that the deaths were a warning that “when dissent turns to violence, it invited tragedy.”

In a strange incident that demonstrated the isolation and disorientation of the White House, Nixon went down to the Lincoln Memorial about 4 a.m. on the morning of May 9, the morning of the demonstration, and spoke with 30 students conducting an antiwar vigil, attempting to convince them of the correctness of his decision to invade Cambodia.

Afterwards, Nixon asked his top aide, H. R. Haldeman, to reactivate the Huston Plan, a proposal for systematic wiretapping, break-ins and other illegal surveillance and harassment of antiwar groups, the forerunner of the “plumbers” group of ex-CIA operatives that conducted the 1972 Watergate break-in.

The greatest fear of the Nixon White House was that the nationwide student protests would intersect with the mass struggles of the American labor movement, following in the footsteps of the events just two years before in France, when student protests in Paris touched off a nationwide general strike that nearly toppled the regime of President DeGaulle.

The Nixon Administration turned to its staunchest supporters in the trade union bureaucracy of the building trades, with New York union official Peter Brennan, later appointed US Labor Secretary by Nixon, organizing a counter-demonstration against protests on New York’s Wall Street on May 8, in which goons organized by the bureaucracy savagely beat antiwar protesters.

But the mass protests nonetheless marked a significant turning point in the conduct of the war in Vietnam. The Nixon White House was compelled to withdraw troops from Cambodia within a month of the invasion, and announced that the pace of troop withdrawals from Vietnam itself would be increased.

A little more than a month after Kent State, Nixon established the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest. This body held hearings at Kent State and elsewhere, and was given the assignment of whitewashing the true cause and the authors of the killings, while giving the impression of evenhandedness and concern. In a September 1970 report, the Commission acknowledged that the National Guard shootings on May 4 had been unjustified, but drew no other conclusions.

No one paid any penalty for the police and National Guard killings at Kent State, Augusta or Jackson State. Eight of the Ohio guardsmen were eventually indicted by a grand jury, but in 1974 a US District Judge dismissed all charges against them, claiming the prosecution’s case was too weak to put before a court.

The enduring significance

The 40th anniversary of the Kent State shootings will be marked, as it has been every year, with events on the Ohio campus organized by survivors of that day as well as other students and faculty. The Kent May 4 Center has established a presence on the internet (www.may4.org). One of its leaders, Alan Canfora, among those wounded 40 years ago, has claimed that a recently discovered copy of a tape recording, archived at Yale University, shows that there was an order to fire given before the shootings, and he has called for the government to reopen the investigation into a coverup of the incident.

While further investigation of Kent State is certainly justified, the real significance of the event goes far beyond the question of whether there was an order to shoot or even whether there was a coverup. Kent State cannot be understood apart from the economic, political and social events of the period that produced this tragedy.

The protests at Kent State did not, of course, arise suddenly or in a political and social vacuum. Mass protests against the US war in Vietnam had been building since 1965. President Lyndon B. Johnson had been forced to withdraw from his reelection campaign in March 1968. The 1968 Democratic Convention had witnessed bloody clashes after Chicago Democratic Mayor Daley had mobilized his police against antiwar demonstrators.

Nor were the antiwar protests simply a student affair. The movement that mobilized literally millions of American youth for a period of nearly five years was part of a broader movement of the working class in the US and all over the world.

In the US, the long postwar boom was drawing to a close. Every section of the working class was stirring, on the issues of wages, inequality, poverty and war. The mass civil rights movement of 1955-1965 had been immediately followed by a series of spontaneous ghetto rebellions involving the most oppressed sections of African-American workers and youth, who demanded that the dismantling of Jim Crow segregation be followed by genuine social equality.

The entire working class, meanwhile, refused to pay for the costs of the Vietnam War through attacks on its wages and conditions. The year 1970 saw the greatest number of strikes in two decades. Just weeks before Kent State, the first-ever national postal strike had led the Nixon Administration to call out the National Guard to move the mail. Earlier, General Electric Co. had been shut down by a militant and protracted strike. Later in the year, General Motors workers walked out.

The response of the ruling class to the militancy of workers and students was immediate. It demonstrated that it was capable of the same ruthlessness at home as that exhibited in imperialist war abroad. Its methods included direct violence, as at Kent State, Augusta and Jackson State, and the methods of provocation, as in the notorious Cointelpro operations that were used to infiltrate movements of students, minority workers and youth. Black Panther leaders Fred Hampton and Mark Clark had been brutally gunned down in their beds in 1969. Malcolm X was killed in 1965 and Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968, and there were many reasons to see the hands of the FBI behind these crimes.

The fate of the protest movement

In marking the anniversary of Kent State, it is necessary to examine the legacy of the protest movement against the Vietnam War. Although it was part of a broader movement of the working class, it never posed the decisive political question that emerged out of this struggle—that the fight against imperialist war required a fight against the system of capitalist exploitation that produced it. That meant a break from the Democratic Party, and a turn by the student fighters against war to the great untapped strength of the working class.

While the working class was held back internationally and in the US by Stalinism and the trade union bureaucracy, the student upsurge was confined to liberal protest and ultimately channeled into the dead-end of the 1972 presidential campaign of Democrat George McGovern.

Those who dominated the student protests, above all the ex-Trotskyists of the Socialist Workers Party, demanded that the struggle against the war be separated from the class struggle as a whole, and from the urgent need to construct a new revolutionary leadership of the working class.

The American Trotskyists, then organized in the Workers League, the predecessor organization of the Socialist Equality Party, fought to turn the students to the working class. The Workers League won the best sections of students to the perspective of building a new revolutionary leadership on the basis of a socialist and internationalist program.

Though defeated in Vietnam, American imperialism still possessed enormous financial and economic reserves, and it was aided by the treacherous policies of the Stalinist bureaucracies in both the Soviet Union and China, and, within the next five years, launched a relentless counteroffensive against the international working class. Beginning with the Carter administration, then spearheaded by Reagan and continued by all of his successors, the bourgeoisie set out to shift the relationship of class forces and to repeal the social gains that had been won in earlier struggles.

As part of this process, a decades-long effort to rehabilitate the war in Vietnam was carried out. The question of Vietnam was posed not as one of imperialist aggression, but rather one of “mistaken” policies. More than a quarter century after the humiliating defeat of US troops in Vietnam, the administration of George W. Bush, with the full backing of the Democratic Party, launched new colonial wars, first in Afghanistan, then in Iraq, wars that continue uninterrupted under Democrat Barack Obama.

Once again, as in the 1960s, the conditions are developing for the reemergence of mass struggles of working people and youth against imperialist war, austerity and repression. The great difference, however, is that the struggles now unfolding take place under conditions of a protracted historical decline of American capitalism.

The United States still dominated the world economy in the 1960s. Today, America is the world’s largest debtor nation, with crippling trade and budget deficits, and the financial collapse on Wall Street in September 2008 touched off the worldwide economic crisis.

The central issue confronting working people, youth and students, posed more urgently today than ever, is the necessity to build a new revolutionary leadership in the working class.