The death of American science fiction writer Ray Bradbury June 5 at the age of 91 in Los Angeles has prompted a good deal of analysis of the author’s work, as well as the rather flimsy claim by some on the political right that he was one of them.

Certainly, Bradbury did declare his admiration for Ronald Reagan and King Vidor’s film version of The Fountainhead (1949—based on the novel by Ayn Rand). In the months before his death, moreover, Bradbury expressed the wish that the upcoming election would see a reduction in the size of government, to be followed by a further reduction “soon.”

Bradbury in 1975

Bradbury in 1975This only demonstrates that the relationship between the conscious political views of an artist and the sense he or she makes of the world through his art is not a simple or mechanical one. Bradbury, something of a “libertarian,” was a self-educated, or as he later put it, a “public library-educated” man, who even in his old age would hold readings to benefit a local library. His work evinces a humanism and sympathy for the oppressed completely at odds with the imbecilic selfishness of the Rand cult.

This is the same man, after all, who wrote stories such as “Way in the Middle of the Air,” from early editions of The Martian Chronicles, about persecuted African-Americans taking to the skies to settle on Mars, away from the bigots. Like so many of his stories, this is a hopeful piece, a search for a solution to a seemingly intractable problem on Earth. It was also a bold story to put out at that time—first appearing in Other Worlds in 1950, before the eruption of the civil rights movement—and shone a harsh light on the prejudice and violence faced by so many.

One might suggest that Bradbury, like other, more prominent literary figures before him, was “compelled to withdraw into the past” (Trotsky) by the conditions of his time. His oft-idealized hometown of Waukegan, Illinois made an appearance in a number of his works. Though generally writing about the future, Bradbury was often reaching back to the past with an almost Hawthorne-esque shake of the head at what science, technology and even desire had wrought.

In his own life, Bradbury rejected much of technology, agreeing only last year, for example, to have one of his books, Fahrenheit 451, released as an ebook. The writer was, not to put too fine a point on it, a bit of an eccentric, even a technophobe. He never learned to drive a car, quite extraordinary for a resident of Los Angeles his entire adult life. Bradbury did not board a commercial airliner until the age of 62.

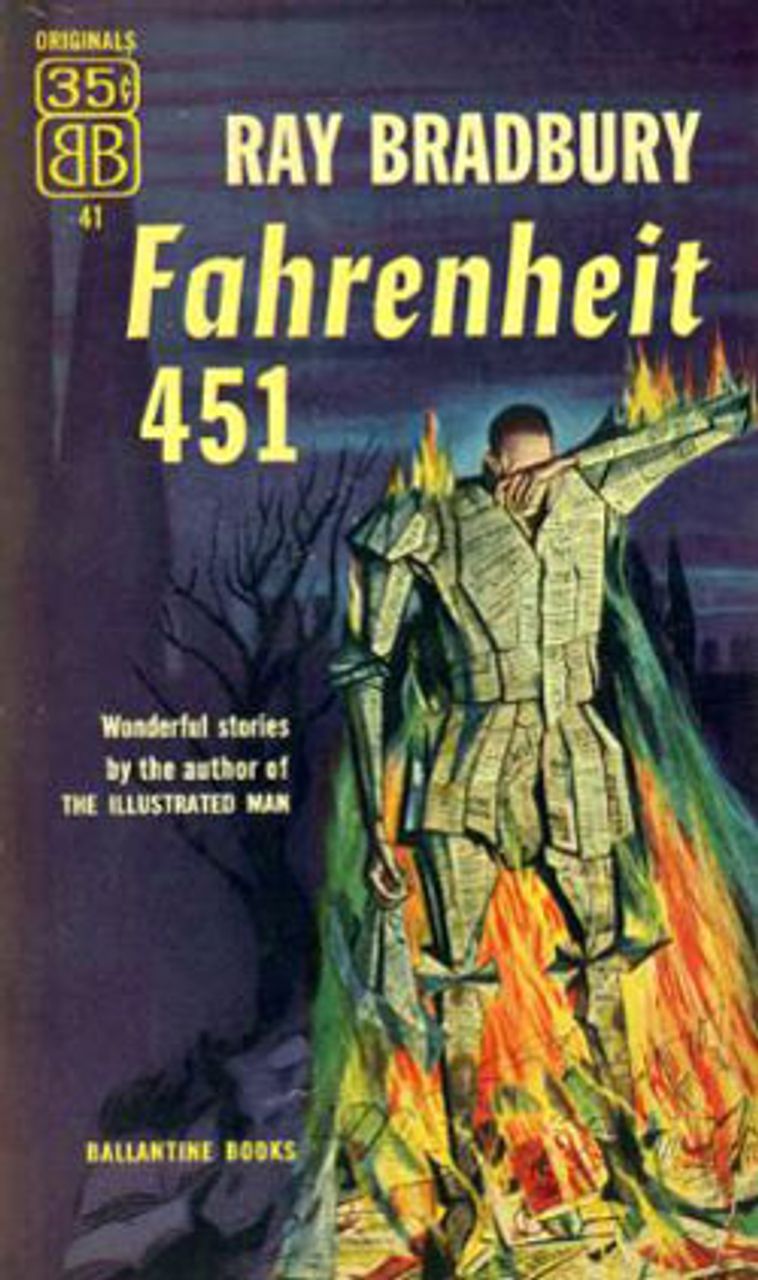

Yet Fahrenheit 451 (1953)—about a future America where books are banned and a fireman’s job is to burn them—is remarkable for its almost predictive qualities when it comes to gadgets such as tiny personal radios, flat-screen televisions and in-ear communication devices.

Bradbury’s writing on occasion even inspired the development of such things. In an interview with Book Magazine in 1998, Bradbury explained, “I’ve never set out to predict. I just write what later seems to evolve and be true.” He continued, “I was in Japan working on a short film, and one of my hosts came to me and put a Walkman on my ears and said, ‘Fahrenheit 451, Fahrenheit 451!’ The young man who invented it had read [about such a device in] the story and decided to build it.”

There can also be genuine pessimism in Bradbury’s works. In Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962), for which he also wrote the screenplay, this comes out quite strongly. The attempts to change what the characters are not satisfied with—in most cases their ages—lead to disaster. Those who do succeed in altering their condition end up dead or enslaved, and the lesson learned by the central characters seems to be to just accept what is.

There was bravery as well in what he wrote. In releasing Fahrenheit 451 at the height of the anti-communist witch-hunt, Bradbury took a significant risk. However, the writer insisted that a statement against McCarthyism was not his intention. Although the novel was viewed and taught for decades as a work aimed against censorship, Bradbury often downplayed the latter issue, and asserted the danger he was warning about was the phenomenon of television.

One can view a video at his site entitled “Bradbury on Censorship/Television” in which the author declares, “I wasn’t worried about freedom. I was worried about people being turned into morons by TV.” When the interviewer notes that Sen. Joseph McCarthy had banned books, Bradbury dismisses this with a casual, “Well, [President Dwight] Eisenhower said put them back, so it was, you know, a few days.” He exhorted librarians to “just quietly put the books back” if censors removed them.

It is doubtful that such comments will stop the use of Fahrenheit 451 as a literary “poster child” for those fighting censorship—after all, Bradbury noted this same thing in a number of other interviews over the years. However it does bring up the question of what happens when an author’s work takes on a meaning not consciously intended by its creator. Fahrenheit 451, far from being a mere complaint against television, is a beautifully wrought work which has inspired generations of free-speech advocates.

In his introduction to Dandelion Wine (1957), Bradbury makes a comment that may reveal more than the writer intends: “It was with great relief, then, that in my early twenties I floundered into a word-association process in which I simply got out of bed each morning, walked to my desk, and put down any word or series of words that happened along in my head.

Bradbury in 1959

Bradbury in 1959“I would then take arms against the word, or for it, and bring on an assortment of characters to weigh the word and show me its meaning in my own life.”

Bradbury was in his “early twenties” in the midst of World War II, the greatest slaughter in world history. Did this and subsequent events have an impact on the writer?

According to Bradbury’s version of things, he wrote instinctively, with his unconscious mind creating the subject and his conscious mind giving it direction. Perhaps, for various reasons, Bradbury was unable to locate himself consciously as an opponent of racism, or McCarthyism. Perhaps his approach was the only way by which he could take on the complex and often grim realities of the time, and offer up his concerns and opposition. He seems to have responded to the difficult present with a series of morality stories encased within a semi-futuristic wrapping.

Bradbury was apparently compelled to project into the future a solution to the problems of racism, the threat of nuclear war, the stultifying atmosphere of the period. It may not be that Bradbury was “repelled” by the new, so much as he was deeply troubled by the post-World War II period. How could he not have felt the impact of the Holocaust, the dropping of bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the onset of the Cold War? Bradbury’s dilemma was one that confronted an entire generation of artists and intellectuals in the US, many of whom turned to the right and helped strengthen a reactionary cultural climate.

Bradbury’s output was remarkable: over 600 short stories, numerous scripts for films and (the loathed) television (including those he wrote for his own show in the 1980s and early 1990s), poetry, nonfiction and children’s books. Most impressive is the quality of the writing itself; he had a tremendous respect for language and brought to the science fiction-fantasy genre a standard to which many subsequent writers have aspired.

Bradbury himself was well read, and inspired by such authors as W. Somerset Maugham and Ernest Hemingway. In an early mantra typed in or around 1947, according to his biographer Jonathan Eller in Becoming Ray Bradbury (2011), he wrote, “Keep chapters to FOUR pages, no more than EIGHT pages. The purpose of a chapter is to contain ONE IDEA! And ONLY one! See Jane Austen! See Tolstoy, Dostoevsky!”

In his own uncompromising approach, Bradbury often found himself at odds, for example, with the writer and anthologist August Derleth, who, as editor of Weird Tales, Bradbury felt was pushing him to produce formulaic work. He resisted and persisted, a struggle from which we have all benefited.